About Siegfried and Mime

or: “By me forged be the sword!”,

or: Leave singers in peace!

This article is linked to my video “Siegfried’s Forging Song (from Wagner’s Siegfried)”, but you can also listen to my interpretation of Siegfried and Mime here:

On fach (again)

My favourite Siegfried started out as a lyric tenor in operetta and Mozart opera contexts before becoming one of the world leading heldentenors (German for “heroic tenor” – somewhat analogous to the concepts of the dramatic tenor or the tenore robusto). While I have been called a “loudness fetishist” before for not being ignorant of the fact that unamplified singing still has to be heard, it’s not just the sheer volume that has convinced me of this tenor’s qualities; more so, it is his intuition of tension and release in both the musical and physical senses, and his overall artistic effectiveness in filling out these kinds of roles. There’s a fascinating pragmatism to carving out dynamics in a style of singing that doesn’t look particularly rich of dynamics on paper, compared to the drastic contrasts in volume and colour that amplified singers often can afford – it somehow shouldn’t be possible to yell for hours on end in a way that isn’t only sustainable, but also intellectually and emotionally engaging to an audience, but that guy is doing it all the time. Having heard him live several times already, it is obvious to me that if he had sung the more lyric repertoire in a similarly ear-shattering way, he wouldn’t have made it very far. This implies to me that we don’t just have a freak of nature who gets to freely sing at twice the volume level that us mere mortals have at our disposal; I very much have reason to believe that my favourite Siegfried is playing by the same rules as we all do, namely the laws of nature. By the way, my scepticism towards the idea that certain techniques or liberties are only reserved for a few lucky individuals is also informed by my experience with learning and teaching a wide variety of non-classical techniques like belting, screaming, whistle register… I’m convinced that all of those sounds can be learned by anyone, even if we have the same strange debates there.

My favourite Mime has sung light lyric and comic tenor parts in opera, as well as oratorio and concert repertoires before taking on this character tenor role – a fach that, especially in the context of a Wagner opera, requires not only high vocal stamina and projection, but also the capability and flexibility to act well at the same time. I’m convinced that just like we value wilful expression and versatility in actors, we should value those same features in singers, and especially in opera singers who sing and act simultaneously. Only few people would argue that an actor’s ability to express a variety of emotions and embody a variety of characters has more to do with “natural talent” or genetic predisposition than with hard work and dedication – after all, that would largely defeat the idea of acting. However, with singers this seems to get more complicated all of a sudden, with teachers, choir leaders, colleagues and basically everyone who has ever read a blog post on “voice type” or “fach” giving unsolicited advice or otherwise trying to participate in shaping the vocal identity of young singers. In this article, I want to explore some of these social dynamics that (especially classical) singers have to deal with, and offer some explanations on how these dynamics may have emerged. By the way, the Siegfried to my favourite Mime used to sing all kinds of baritone repertoire ranging from opera to art song for several decades before exploring the tenor range, and even in his sixties he continues to extend his tessitura upwards.

Once you start digging a bit deeper, or even just keeping your eyes open for these kinds of stories, it gets harder and harder to treat them as exceptions to the rule; I would even go so far as to say that there are much more cases of singers who, by delivering high quality singing in more than one fach or even voice type, defy the biologistic myth of fach being solely predetermined by their physiology than there are singers who actually stuck to exclusively one fach throughout their career. There’s many examples of female opera singers who have changed their fach or voice type – in fact, the Wikipedia article on voice type lists mostly female examples of voice type changes, but some of the most prominent examples are male: there’s the Spanish tenor who started out as a baritone, later sang all kinds of tenor repertoire, and now has gone back to baritone land; there’s the American opera singer who markets himself as a baritenor and has already sung all kinds of repertoire from bass-baritone over light lyric tenor to dramatic tenor with great success. Don’t let the fact that these examples are famous (most of you probably know which singers I’m talking about even though I’m not naming any of them) distract you from the countless not-so-well-known ensemble singers and freelancers who often have to sing a wide variety of roles. My favourite Mime is one of those, and based on my experience of having attended 75 opera performances in 13 different houses between 2022 and 2025 – yes, this does qualify as an obsession – I will argue that some of the best and most versatile vocalism is done by singers who are not famous at all.

While one could argue that just this alone should already make it clear that fach is more of a job title than a biological limitation, I am aware that many arguments can be made against this: singers can get “mislabeled” or “miscast” before they find their “true voice”, voices can change and develop over time, most repertoire allows a little leeway in how lyric or dramatic exactly it can be sung, some singers “destroy” their voices singing out of fach and so on. While the first of these points is probably the most disputable (after all, a claim like this can really restrict a singer’s vocal identity and career, so one would hope that the people who perpetuate it had very firm evidence, which is not the case), I have already addressed the myth of the “natural”, “true”, or “unmanipulated” voice in my video “Quick Tip | #3 Voice Type & Vocal Fach”, and thus want to focus more on the other aspects here – specifically the “moving the goalposts” style argument that “Fach is predetermined, and if it changes it must be because of ageing, and if that’s not the case, it will inevitably lead to vocal damage or technical deterioration at some point”. When we say that voices can change and develop over time, can we be sure that what we’re observing is purely of biological nature, and that singers can only passively observe and obey this unswayable process? Or do singers, perhaps, have some agency on this if you feed them knowledge on how voice production works instead of vague predictions and unscientific (or worse: pseudo-scientific) esotericism? I much prefer the latter idea, and it matches quite well with my own experiences as a singer and teacher, as well as those of many of my friends and colleagues.

I will give you some insights into my own vocal journey, share my thoughts on feedback culture, hierarchies and overall social dynamics in classical singing, and pass on some of the anecdotes that professional classical singers have told me about this topic.

My vocal journey

I started exploring classical singing about five years ago – apart from some very rudimentary choir and art song experience before that. Having been self-taught until age 18, I had sung mostly rock and metal (as well as some jazz, pop, and musical theatre later in conservatory context) until that point, and I didn’t have any good intuition for how to produce classical sounds. I did, however, have some intuition on how it was supposed to sound, and how classical music worked in general due to my experience of having played the violin from age six on, as well as the piano from age ten on. What happens when a self-taught belter and screamer develops a special interest for classical singing, and especially opera? In my case, the way I had previously thought about “chest voice” – a somewhat heavy coordination that increasingly relies on megaphone-style shaping (twang, higher larynx and wider mouth opening), and an overall rising intensity (higher pressure, effort, and volume levels) when being taken into the higher range – informed my idea of classical chest voice too, resulting in my first attempts of operatic singing being very powerful and somewhat ringy, but lacking darkness and general coherence. When I started learning more about resonance tuning, it did not only allow for darker sound colours without compromising effiency or ring in operatic singing, but it also improved my non-classical singing and teaching (make no mistake though: no classical teacher had ever taught me these concepts). However, whenever I didn’t hit the perfect tuning, my larynx would still shoot up in an uncontrolled attempt to ensure efficiency via the megaphone strategy. You can hear my best efforts to sing with (or against) these complications in my 2023 rendition of “Nessun Dorma”.

When I first discovered the possibility of using hyper-compression (essentially, a stiffer abdomen and constricted false folds) with an operatic sound colour at the end of 2023, it seemed like all of my problems were suddenly solving themselves: this more linear way of producing sound allowed me to reach and sustain high notes without relying too much on resonance tuning, so it basically felt like a superpower. Sure, good vocal tract shaping still helped me achieve higher volumes with more ease, but I didn’t crack or strain anymore whenever something wasn’t perfectly precise. This shortcut, and the fact that most people even preferred the sound of my “technique 2” over even my best “technique 1” attempts, led me to rely on hyper-compression for any operatic note higher than A4, and even as low as D4 in some of my recordings. Not focusing on the non-compressed approach for more than half a year resulted in all of my muscle memory for “operatic sounds” being replaced by “technique 2” (including my vocal tract shaping, my posture and the abdominal stiffness), and when I revisited “technique 1” at the end of 2024, I noticed that my high range didn’t work anymore. I spent the rest of 2024 focusing exclusively on “technique 1” again, and started cross-training both approaches in 2025 until both worked without compromising each other. My high range in “technique 1” is back now, but in order to prevent my larynx from uncontrollably rising or “technique 2” artefacts sneaking in, I have been temporarily working with a compressed tongue and less twang than previously, resulting in a somewhat “woofy” or “stuffy-nosed” sound – which I will solve as soon as I’ve completely overcome the other habits. For that reason, all of my operatic high notes in this year’s cover series are still hyper-compressed.

Now, why do I explain my training plan in such detail? I’m trying to remind you that my singing abilities aren’t luck or coincidence, that progress isn’t always linear, and that the fastest way to improve isn’t always the most linear way. I could fill a whole other video telling you about my belting and screaming journeys too, but I want to focus on operatic singing here because only in classical singing do we tend to have the paradox duality of perfectionism (“If you can’t sing it the best way possible, don’t sing it”, “Nobody will ever come close to the Golden Age singers”…) and ineffiency (“Learning to sing takes at least a decade”, “You shouldn’t attempt this role at such a young age!”…). To me that seems very contradictory, but probably if you’re exposed to those ideas all the time, you develop the belief (or hope?) that somehow it makes sense: it’s almost a warped, demotivating version of “The journey is the destination”, and it can result in some very strange interactions:

When I posted my rendition of “Donna non vidi mai” last year, an acquainted opera singer couldn’t believe it was my actual voice (“If that was really you, you’d be one of the best singers on this planet”), publicly accused me using an AI model of Mario Del Monaco’s voice (which I take as a huge compliment), explained that my height and overall physique couldn’t possibly produce these kinds of sounds and only reluctantly back-pedalled after I had sent him some voice messages of me singing live. Apparently to him, it just seemed impossible that someone in their 20s could already have achieved that level of proficiency with these kinds of sounds – let alone after less than five years of training. On the other hand, since the first day I’ve started sharing my operatic singing, I’ve received plenty of unsolicited (and often not very helpful) feedback from classical voice teachers, singers, and armchair critics that can neither teach nor produce these sounds. I don’t always suspect bad intentions, and some of these people I consider my friends regardless, but I want to draw attention to the fact that I’ve only very rarely experienced similar things in the context of non-classical singing or vocal pedagogy so far – why is that?

A vicious cycle

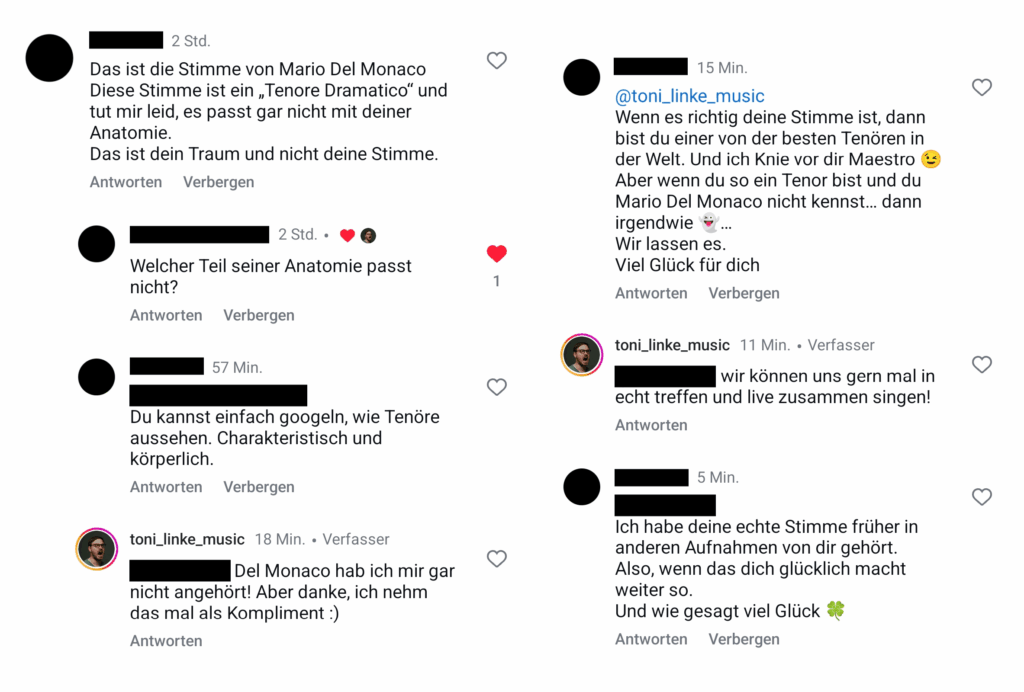

A similar thing that only ever happens in classical singing is that people will give their (again, unasked) opinion, advice, or remote diagnosis on what fach someone “is”, or what repertoire they should stick to. So far I’ve been labelled a light lyric/leggero tenor, a full lyric tenor, a lyric-dramatic/spinto tenor, a dramatic tenor, and a baritone. Here’s just a couple of screenshots from social media – about a third of the opinions I’ve heard up to this point:

By the way, based on this compilation about half of those people seem to agree that I “am” a spinto tenor; likely this has to do with the fact that most of the operatic arias I sing are spinto repertoire – not very suprisingly, most of the “leggero” comments I get are in reaction to me singing leggero repertoire, almost as if singers can adapt their techniques to different styles!

Anyway, I’m by no means implying that all classical singers or pedagogues do these things – in fact, I know many classical singers that are just as critical of those phenomena as I am – but I truly believe this is unique to classical music, and operatic singing in particular: “Not all opera singers, but always opera singers”. “Real” opera singers report similar or worse experiences to me, and I suspect a common motive: to exert power over other singers. Power over their identities, power over their vocal journeys, power over their careers. If you are a classical singer and up in arms by now, let me try to appease you: the abused becomes the abuser – the only reason why so many classical singers (consciously or unconsciously) participate in these kinds of power games is that they feel powerless themselves; they have often been deprived of self-efficacy, self-reliance, and self-confidence by people who have or had power over them (like their voice teacher, or their choir leader, or their audition jury, or their musical director…). If you’re not a classical singer and still sceptical, let me give you some examples of how bad it really is – this is what some of my friends and colleagues have told me:

“One of our conservatory voice teachers told her students that they’re not allowed to get any other vocal teacher’s input; at the same time, several of her students got serious voice problems during their studies with her and had to secretly take extra lessons with other teachers for damage control (with one of these other teachers actually locking his door during lessons so his colleague wouldn’t notice the ‘adultery’). During my studies, I was told that I was a baritone, a tenor, and even that I’m ‘not a singer type’. I professionally sing lyric tenor repertoire now.”

“I was studying in one of the two biggest conservatories in France, one of the most prestigious in Europe. My teacher was a dramatic soprano who had had a short but eminent career. A large portion of the classes were dedicated to her stories about how wonderful she used to be, what wonderful contracts she had, what wonderful albums she recorded etc. If we had the bad idea to bring some French repertoire, a significant part of the lesson time would be spent discussing the pronunciation of the French ‘silent e’. One day, after almost two years of lessons and making no progress with my high notes (to be honest, no progress whatsoever on any technical topic), she just said ‘for high notes, ask your girlfriend to stick a finger up your ass.'”

“During my studies at a big German academy, a famous Wagnerian soprano became a professor for voice there. She made her students force their tongues down with a spoon. She had an amazing career but absolutely no clue about vocal technique – and yet she still wasn’t as bad as my professor… Two things she said really stuck with me: ‘You know, every voice has an end’, after I had accidentally sung a tenor high B flat in her lesson. She would never have me try it again, not even once – felt so weird. And later, when I showed her my tenor high C sharp, D, and E flat: ‘These are just circus stunts or party tricks’. She just wanted me to be a bass-baritone, no matter what my wishes and possibilities were. When I finally decided to leave her class after four semesters, I was approached by many other students and teachers telling me how fortunate I was for having left her class as apparently she had been notorious for wrecking voices for years. Nobody had warned me before, but some said they were surprised by how long I had endure her method. The semester I left her, three other singers left too for similar reasons.”

“When asked about support, my teacher at music uni told me that my pelvic floor must feel like ‘I don’t want to let my boyfriend’s dick escape'”

“Back when we were in conservatory, a tenor friend’s dramatic soprano professor would make him go up completely spread. He’d lose his voice entirely after a half hour of screaming wide open As and Bbs in the lessons, then she would say the problem was that he wasn’t supporting hard enough and do all kinds of crazy body exercises to get him to push harder. When he would try lowering the larynx a bit and it would get easier and objectively better it was practically bullied out of him by her. A very strange dynamic indeed which lasted 7 years! Luckily my own professor was merely neglectful and I was left largely to my own devices to experiment, even if those were mostly dead ends.“

“My first singing teacher told me that it’s normal to leak a bit of pee in the most intense vocal moments.”

I’ve heard plenty of stories like these, and I’m by no means the first to share them. Again, I’m not trying to imply that classical voice pedagogy is always terrible, or that non-classical voice pedagogy is always better; in fact, my point isn’t even about pedagogy specifically, it’s about tendencies in the overall culture. The reason half of my vocal covers are opera arias even though I teach mainly rock and metal singing, the reason those arias range from dramatic baritone to light lyric tenor repertoire, and the reason I have decided to sing both Siegfried and Mime (two roles that are supposed to sound very different from each other) in this video here is that I believe the only way to dismantle these dynamics is to do exactly what classical singers are often being discouraged from: to do what they want to do, think what they want to think, and sing like they want to sing. If this is controversial, that just means more people have to do the same thing until it isn’t controversial anymore.

By the way, of course you are still free to dislike my singing in this video, in other videos, or in general. In fact, I would be delighted if we could all agree that singing, and art in general, is first and foremost a matter of taste, and I would prefer people to just appreciate that singing makes them feel things (positive, negative, or ambivalent) instead of coming up with half-baked rationalizations about why their deeply subjective perspective is actually objective. I say this not although I’m a voice teacher, but because I’m a voice teacher, and I am convinced that the classical singing bubble can become less toxic and exclusive, and more welcoming and culturally relevant if we want it to.

No responses yet